In the last weeks we struggled with server stability. As written before, the critical, resource-heavy and publicly available tasks have for a long time been the generation of timelines (and thus complicated search queries) and on the other hand those involving the processing or generation of large files; namely the IIIF API and PDF generation.

In the last post, I detailed how we severely restricted the availability of the public PDF generation functionalities in museum-digital according to available system resources. That, as it turned out, was not enough to bring reliable stability to our systems. After the server fell over on December 26th once more, we hence moved the IIIF Image API into the same PHP setup used for PDF generation – meaning that any user/IP can only request the API 10 times a minute and that for any instance of museum-digital, only one PHP worker serves it. This allowed us to severely reduce the maximum available resources per worker for the frontend outside of those two use cases (where the IIIF Image API may use up to 80 MB of RAM, no other part of the frontend will go beyond 5). Since then, the system runs as smoothly as if AI scraping had never become an issue.

A Limited Goodbye to IIIF & Server-Side Image Manipulation

Now, what does that mean in practice? On the one hand, we have not fully removed the IIIF image API. All links generated using it remain valid and will be served, even if comparatively slowly.

On the other hand the user experience with viewing the images in a IIIF viewer will be significantly worse, even though this strongly depends on the IIIF viewer. The most popular “full” IIIF viewers being Mirador and Universal Viewer, significant problems (or a complete inability to use an object’s images) are to be expected with Mirador. Mirador in its default configuration loads multiple segments of an image separately to then assemble the displayed image from those – with the creation of the segments happening on the server, thus consuming resources centrally. It also seems to set extremely low limits on accepted response times, which museum-digital’s IIIF Image API now regularly exceeds due to the aggressive rate limiting. Simply looking at the demo installation of Universal Viewer, the software seems to be much more targeted in its API calls and might still work well despite the restrictions.

As far as I know, there are no published numbers on the market share of the different IIIF image viewers. And about whether IIIF viewers external to whoever provides the API are actually regularly used or not. The most jaded – and likely true – assumption would be that the share of users who use IIIF without a viewer hosted next to the API is miniscule and that most users will use one of the abovementioned. Our experience, once again, seems to support that hypothesis: We released our implementation of IIIF 2 in 2020, but essentially nobody noticed before we also started hosting a IIIF viewer.

As we do use Mirador as a viewer, assume the “visible” IIIF image API at museum-digital to be more or less broken. Developers and those making direct use of the API without our installation of Mirador can still benefit from the API. But those are comparatively few.

The radical restriction of resources provided to the IIIF Image API is thus likely indeed a goodbye to IIIF, if a limited one. The basic idea is great – to create a unified way to reference parts of an image (or later a wider media file) and annotate it. In times of significantly increased bot activity, reduced funds, and foreseeably rising hosting costs, our example may be an early sign that the decision to realize that aim by specifying an API to be implemented by the data providers restricts the ability to fully support IIIF to very well resourced institutions. And as funds are shrinking, that is less and less institutions. Let’s hope that the most basic need IIIF wished to fulfill can be achieved in a different way in the future; one that is accessible to anybody. Realistically this means that computing would need to happen on the client PCs, not on a server.

To end the saga on a more positive note: Since we limited the IIIF Image API, our systems run wonderfully smoothly again and we were able to reduce the overall rate limiting on the rest of museum-digital’s portals. We will monitor the situation and increase the limit slowly to allow more simultaneous API requests without risking stability.

Communications

Second, the whole ordeal posed a challenge to our communication channels. If any significant error occurs anywhere on museum-digital, I personally am sent an encrypted error message via mail. Usually. In this case, the primary component falling over was the PHP server, which is also responsible for managing the sending of mails. If a service fell over, the primary way to learn of it was receiving mails about that instead. Reaction times were thus worse than they needed to be. This means that we need to improve our monitoring.

On the other hand there was the issue of explaining what was going on. We had a thread about it in the forum, which few people read. We had the blog posts. Which few people read. We lack (or lacked) a unified source of information about current events that we can assume people to read. The blog could and should be exactly that.

At the top right of the login screen of musdb, the two most recent blog posts from the respective region as well as from the “development” category of the blog have been shown for years. Then we turned on the “remember me” feature by default, which means that people only very rarely see the login page at all anymore.

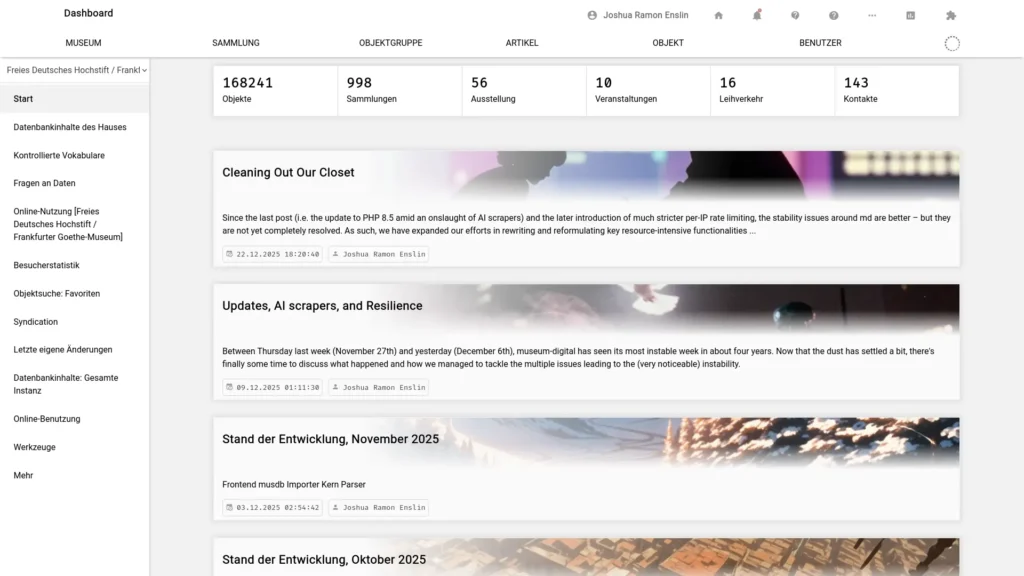

The first page most users see upon logging in or opening musdb while logged in is the dashboard, the default subsection of which previously offered a summary of the database contents a user has access to, a tile for writing personal notes to oneself, a tile with messages from the respective regional administrators, a tile for the integration of a discourse forum, and links to the museum elsewhere on the web.

The summary of database contents and the links to the museum elsewhere are certainly useful. The other features not so much. Checking their actual use revealed that barely anybody used any of the note-taking features (likely also because musdb itself offers better alternatives elsewhere), while the discourse integration has not been in use for years. The very first features one sees when opening musdb were thus largely unused, wasting space that could be filled with a feed of relevant blog entries.

And so we removed the unused features and replaced them with a more prettily designed feed. This feed now contains the two newest blog posts from the development feed in the user’s language, the regional or national feed (again in the user’s language) as well as – importantly – the English-language development feed. None of the most recent development-related posts were translated to any language other than the original English, mainly because the time was better spent trying to alleviate or fix the issues than describing them in yet another language. Besides, most people know enough English to grasp the posts. And for those who do not: Community contributions to the blog – also translations for those who do not – are always welcome.

Mentions

Between 6 a.m. and 9:15 a.m., museum-digital’s main server unfortunately experienced another outage. The immediate outage has been resolved now. The larger issue remained the…

December 2025 was an interesting month for museum-digital. An update to the PHP version used as well as a flood of requests by what is…

Az elmúlt hetekben a szerver stabilitásával küzdöttünk. Ahogy korábban írtuk, a kritikus, erőforrás-igényes és nyilvánosan elérhető feladatok hosszú ideje az idővonalak generálása (és így a…